War Photography and it’s Psychological Fabrication

War photographers, while usually imagined as a cliché loner for Hollywood archetypes with machismo, are a bit more nuanced than we give them credit for. Though they have given us various life-changing examples of war during earlier years, society often forgets the trials and psychological effects that are bestowed upon them from their times at war. From post-traumatic stress and depression, war photographers are historically just as much soldiers, as any other enlisted combatant. The images that each war photographer delivers, albeit emotionally staggering, are images that have not only changed the photographer, but also the viewers as well. Photographs of war have impacted society in various different ways, from photographers and soldiers to the civilians living on the home-front. In this essay, I will discuss the different types of war photographs that have altered viewpoints of the generalized public, and their efforts in changing the standardized view of war.

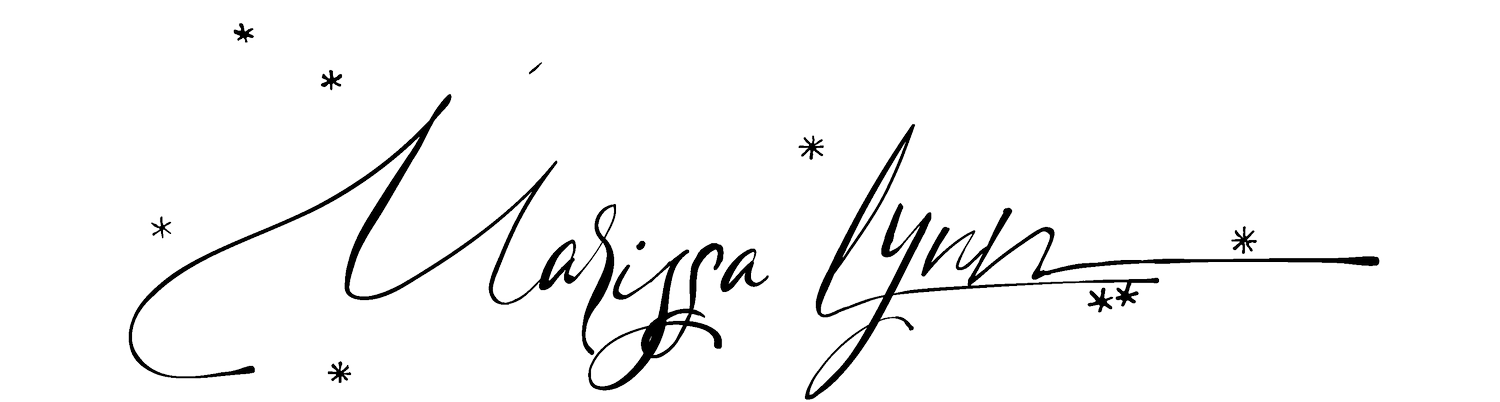

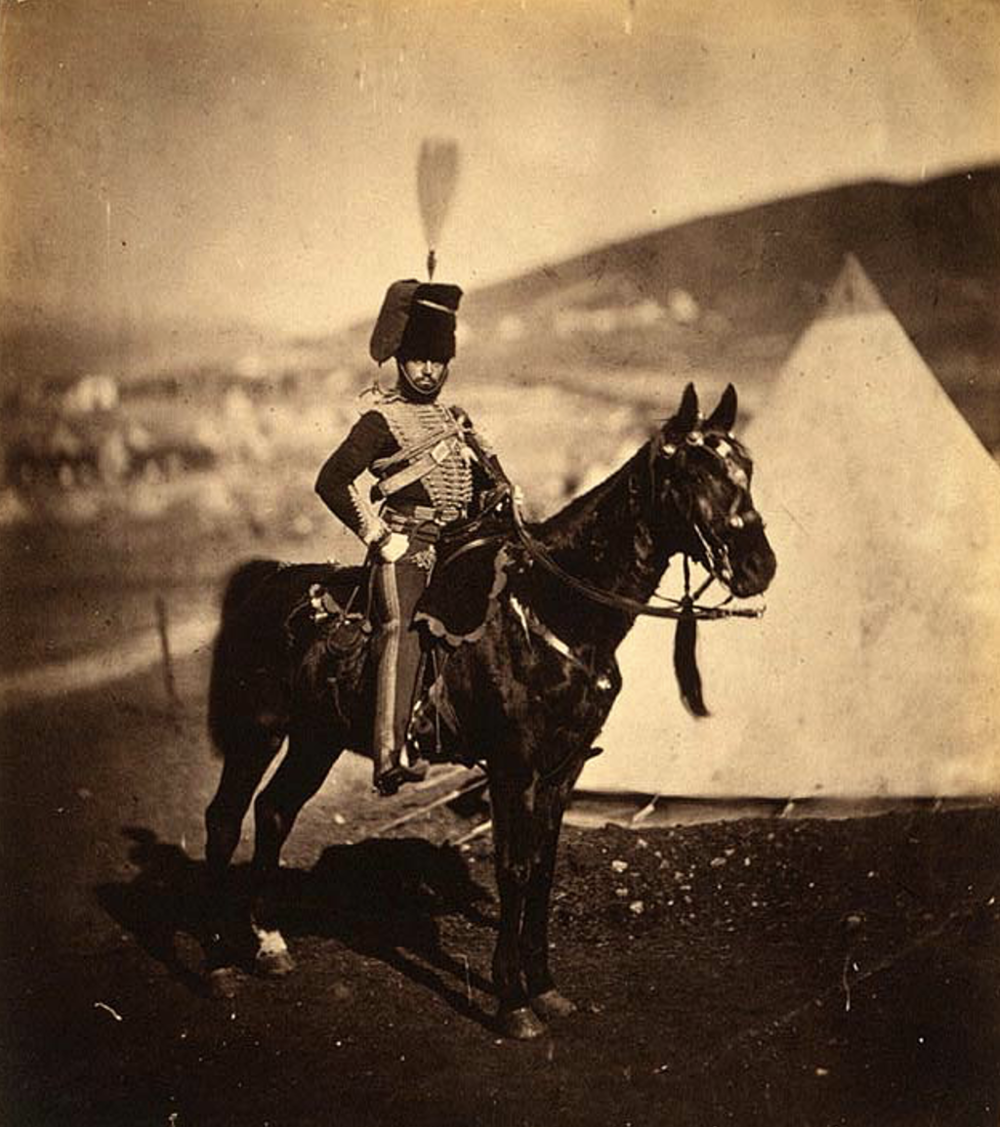

In the first documentations of war photography, an unknown daguerreotypist travelled with the U.S. military during the Mexican American War of 1846. While these images give a slight peek into the warfront, the delicacy of the photography equipment during this time was unable to capture any active battles. Despite this fact, encampments and portraits were some of the first images to portray war to the public outside of paintings and recounted stories. Bernd Hüppauf writes in his essay, The Emergence of Modern War Imagery in Early Photography, that “it can be argued that after hundreds of years of battle painting which, with few exceptions, was devoted to heroic images of war, it was the ‘democratization of images’ through photography from mid-nineteenth century onward that exposed the moral question of war as one of pictorial representation.” Roger Fenton, one of the first known photographers to capture war, photographed over five hundred images of the Crimean War in the 1850’s. Fenton’s images included scenes of various landscapes, battlefields, camps, as well as some portraits of officers and soldiers. In his photograph, Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855), one of his more famous images, an empty and dusty road is devastated by cannon balls. Although this photograph is widely accepted as staged to emphasize the destructive powers of war, many still honored Fenton for his documentation. The subtle symbolism, albeit staged, not only showed the implied threats of war, it also showcased the immense power that war can have on a single area. While the lack of heroism in this photograph disassociates the viewer from the winning or losing side, Fenton’s use of pictorialism in this scene of rolling hills also creates a less devastating image emotionally for the viewer so that it is easier to comprehend the effects of war during this time. In another one of his works, Injured Zouave, the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg is depicted by a dead soldier. Later to be revealed as staged, this image proved to strike an emotional chord among the home-front on another level for the devastation of war. Prior to war photography, most of the depictions of war to the public fell to documenting the clean-cut heroes of the winning sides. These war photographers brought life to the realities of death and devastation for the general public that ends up altering every view of war that was originally held.

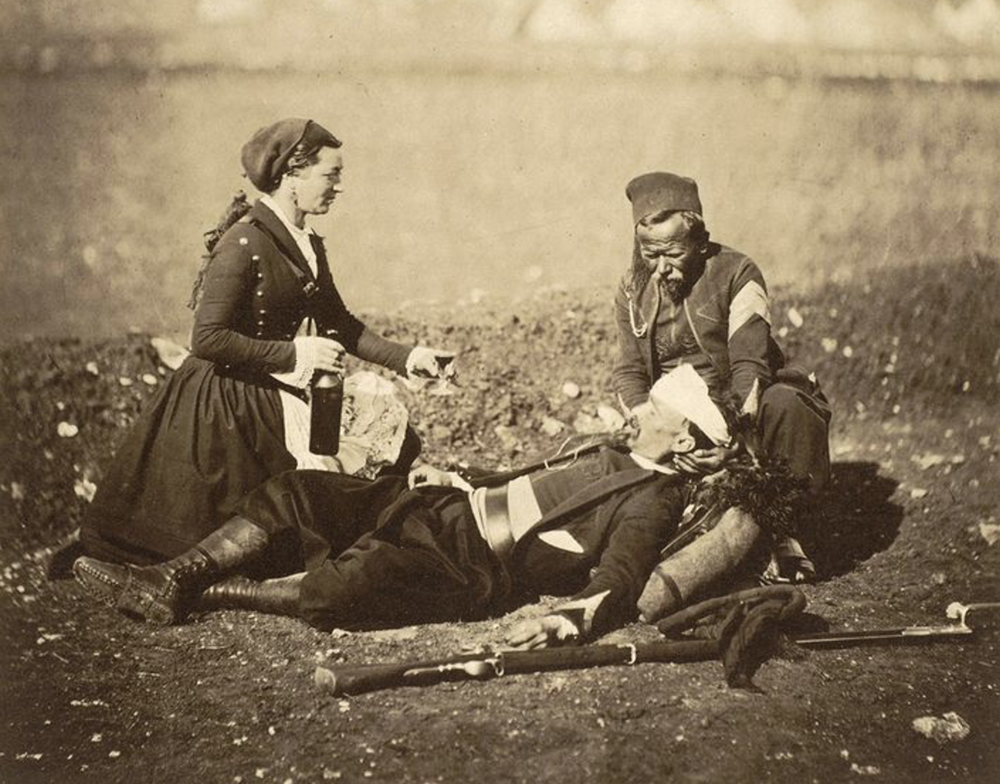

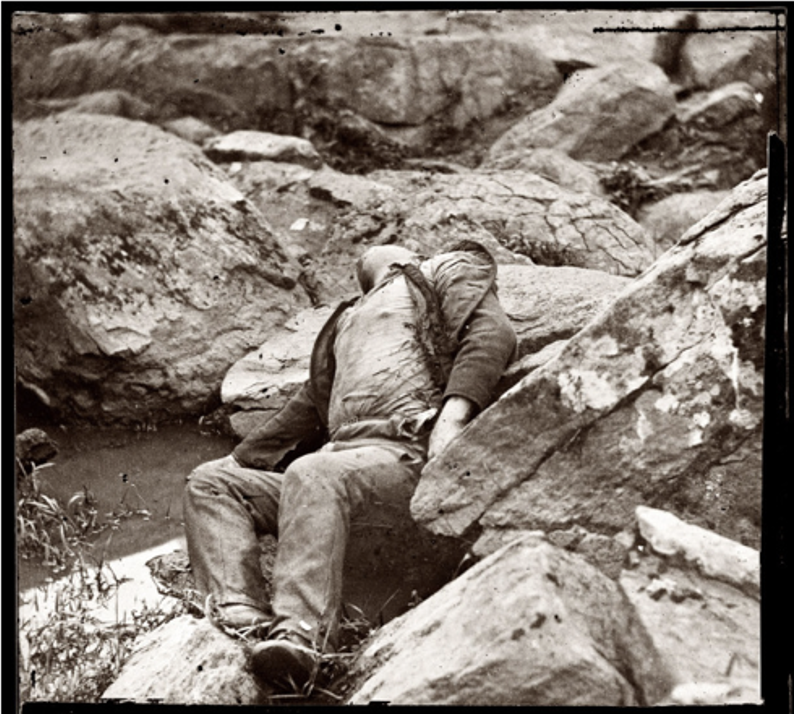

In later years, during the American Civil War of 1861, a new war photographer named Matthew Brady ventured out onto the fields with a new mobile photography studio. While this equipment seemed more feasible, it was still rather difficult for field photography to be captured. Because of the rather arduous issues of photography equipment during this time, combat photography was still unable to be captured. Brady’s photographs, albeit fabricated, posed various different scenes of war photography throughout his time with the Civil War in order to relay information back to the home-front. While these photographs were intended to be mass-produced for consumption by the generalized public, many of these images were not considered true representation of war due to the mass fabrication of these images. One of the more renowned images included Alexander Gardner’s Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, where he posed the body of a fallen soldier with a rifle. This commercialized image, while powerful and moving in his position and setting, exploited the power of realism perceived in this shot, and shaped the public’s opinions towards war and death. To civilians, these collective photographs where a window into the warfront and the lives their family and friends were taking part in. “The impact of shocking and gruesome photographs on public memory and imagination,” Bernd Hüppauf writes, “could not be matched by painting or drawings simply because of the perceived authenticity of photography.” In Emily Godbey’s essay, she regards war images as a horrific aftermath and chilling visions. Godbey initially expresses in her essay that the civil war photographs taken during this time were “horrific records that transfix as much as they repel,” while talking about the war scenes and portraits of the dead (265). Such a great way to summarize her entire topic, she almost seems as entranced by this topic as the civilizations did during the first productions of these images. Partial to that, her quote that these photographs were “[linked] to erotic imagery, …[to] allow the viewer to see what is normally hidden” is more than a out of the box way to view these images (270). This quote, while a view shattering moment for me, changed the way I think of war photography. Eroticism, while a intimate term, is not usually the first word that pops to mind when thinking of death and destruction. However, Godbey’s use of the term makes complete sense in this instance due to the privacy and overall fascination of these intimate moments. Onlookers of the more modern stereographs, would bring opera glasses, or complain about the lack of blood and gore throughout the presentations of these photos, as if they were nothing but a fictional scene. These stereographs, while able to create an almost life-like effect, were used as a way to make a real life tragedy into a worldwide spectacle.

In today’s society, modern warfare photography is consumed with more urgency and rapid intake. While a bit more strategic and dangerous than earlier years, the shocking imagery has become something of commonality in the eyes of today’s generalized public. From the explosive imagery of mass graves and destruction, we, as a society, have become more than attuned to the familiarity and reality of war. Not only have these devastating landscapes and mourning soldiers found their place in our mind space, they have also impacted our everyday life.

LIST OF IMAGES

Roger Fenton’s The Valley of the Shadow of Death (1855) © Royal Collection Trust; Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Theodore Gericault. Raft of the "Jellyfish" (Le Radeau de la Méduse). 1819. Louvre Museum, Paris

Roger Fenton. Injured Zouave, Crimea. 1855

Alexander Gardner, Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg from Gardner's Photographic Sketchbook of the War, 1865

Stereograph of dead in a ditch, Antietam.

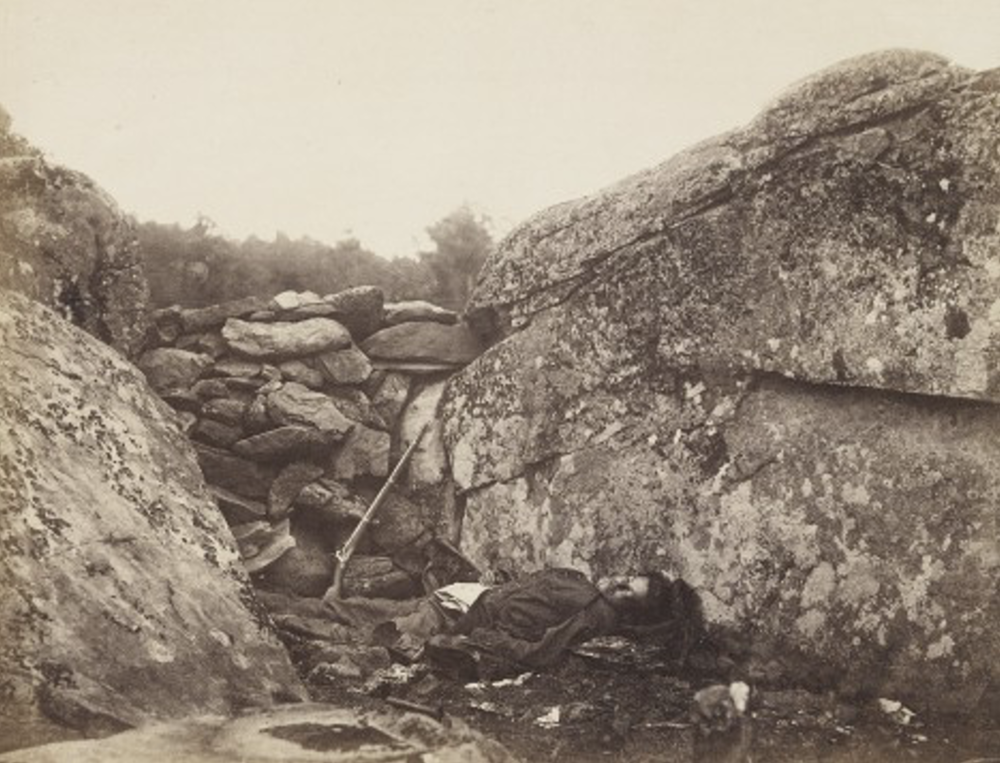

"Stone Church, Centreville, Va., March, 1862" (Gardner, Plate 4).

Roger Fenton’s “shell shocked” Lord Balgonie (1855) © Royal Collection Trust; Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

Distant view of Sevastopol from the front of Cathcart's Hill. LC-USZC4-9260

Cornet Henry John Wilkin, 11th Hussars. LC-USZC4-9124

Dead Confederate sharpshooter at the foot of Little Round Top, Gettysburg 1863

WORKS CITED

Allen, Craig. “Photographers on the Front Lines of the Great War.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 30 June 2014, lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/06/30/photos-world-war-i-images-museums-battle-great-war/.

Battlefields.org. “Photography and the Civil War.” American Battlefield Trust, 9 Sept. 2019, www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/photography-and-civil-war.

Cohen, Alina. “The Physical and Psychological Toll of Photographing War.” Artsy, Artsy, 15 Jan. 2019, www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-physical-psychological-toll-photographing-war.

Departments of Photographs, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Photography and the Civil War, 1861-65.” Metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Oct. 2004, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/phcw/hd_phcw.htm.

Fenton, Roger. Roger Fenton, Photographer of the Crimean War; His Photographs and His

Letters from the Crimea. New York: Arno Press, 1973.

Gallman, James Matthew, and Gary W. Gallagher. Lens of War Exploring Iconic Photographs of the Civil War. Univ. of Georgia Press, 2015.

Godbey, Emily ‘Terrible Fascination’: Civil War Stereographs of the Dead, History of

Photography, 36:3, 265-274, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2012.672225, 2012.

Horan, James D. Timothy O'Sullivan: America's Forgotten Photographer. Bonanza Books, 1970.

Hüppauf, Bernd. “The Emergence of Modern War Imagery in Early Photography.” History and

Memory 5, no. 1 (April 1, 1993): 130–51.

O'reilly, Finbarr. “Beyond the Myth of the War Photographer.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 18 Dec. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/12/18/lens/shooting-war-photograper.html.

Rosenheim, Jeff. Photography and the American Civil War . New York, N.Y: Metropolitan

Museum of Art, 2013.

Trachtenberg, Alan. “Albums of War: On Reading Civil War Photographs.” University of California Press.